grep [options] [regexp] [filename]

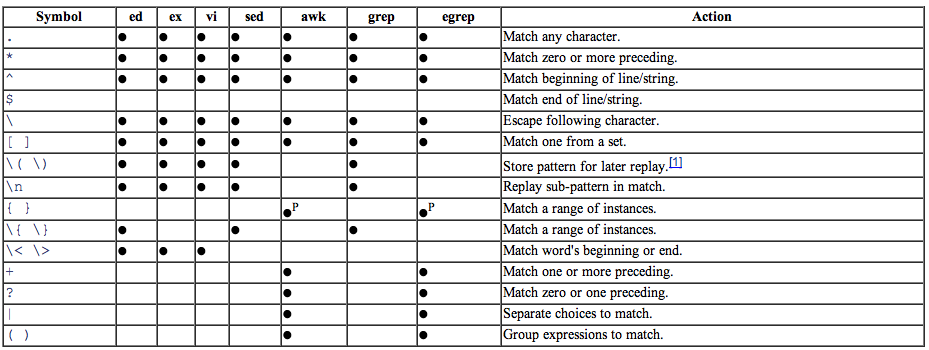

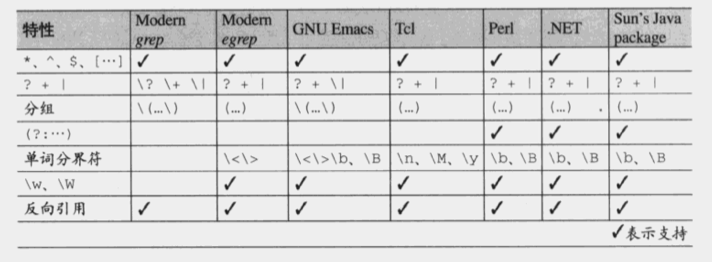

Regular expressions are comprised of two types of characters: normal text characters, called literals, and special characters, such as the asterisk (*), called metacharacters.

using the single quote underneath the tilde key (also called the backtick) tells the shell to execute everything inside those quotes as a command and then use that as the string. grep `whoami` filename

With double quotes, it be- comes possible to use environment variables as part of a search pattern: grep "$HOME" filename

Match Control

-e pattern, --regexp=pattern grep -e -style doc.txt

Ensures that grep recognizes the pattern as the regular ex- pression argument. Useful if the regular expression begins with a hyphen, which makes it look like an option. In this case, grep will look for lines that match “-style”.

-f file, --file=file grep -f pattern.txt searchhere.txt

Takes patterns from file. This option allows you to input all the patterns you want to match into a file, called pattern.txt here. Then, grep searches for all the patterns from pattern.txt in the designated file searchhere.txt. The patterns are additive; that is, grep returns every line that matches any pattern. The pattern file must list one pattern per line. If pattern.txt is empty, nothing will match.

-i, --ignore-case grep -i 'help' me.txt

Ignores capitalization in the given regular expressions, either via the command line or in a file of regular expres- sions specified by the -f option. The example here would search the file me.txt for a string “help” with any iteration of lower- and uppercase letters in the word (“HELP”, “HelP”, etc.). A similar but obsolete synonym to this op- tion is -y.

-v, --invert-match grep -v oranges filename

Returns lines that do not match, instead of lines that do. In this case, the output would be every line in filename that does not contain the pattern “oranges”.

-w, --word-regexp grep -w 'xyz' filename

Matches only when the input text consists of full words. In this example, it is not enough for a line to contain the three letters “xyz” in a row; there must actually be spaces or punctuation around them. Letters, digits, and the underscore character are all considered part of a word; any other character is considered a word boundary, as are the start and end of the line. This is the equivalent of putting \b at the beginning and end of the regular expression.

-x, --line-regexp grep -x 'Hello, world!' filename

Like -w, but must match an entire line. This example matches only lines that consist entirely of “Hello, world!”. Lines that have additional content will not be matched. This can be useful for parsing logfiles for specific content that might include cases you are not interested in seeing.

General Output Control

-c, --count grep -c contact.html access.log

Instead of the normal output, you receive just a count of how many lines matched in each input file. In the example here, grep will simply return the number of times the contact.html file was accessed through a web server’s ac- cess log. This example returns a count of all the lines that do not match the given string. In this case, it would be every time someone accessed a file that wasn’t contact.html on the web server.

--color[=WHEN], --colour[=WHEN] grep -color[=auto] regexp filename

Assuming the terminal can support color, grep will color- ize the pattern in the output. This is done by surrounding the matched (nonempty) string, matching lines, context lines, filenames, line numbers, byte offsets, and separators with escape sequences that the terminal recognizes as color markers. Color is defined by the environment vari- able GREP_COLORS (discussed later). WHEN has three options: never, always, and auto.

-l, --files-with-matches grep -l "ERROR:" *.log

Instead of normal output, prints just the names of input files containing the pattern. As with -L, the search stops on the first match. If an administrator is simply interested in the filenames that contain a pattern without seeing all the matching lines, this option performs that function. This can make grep more efficient by stopping the search as soon as it finds a matching pattern instead of continuing to search an entire file. This is often referred to as “lazy matching.”

-L, --files-without-match grep -L 'ERROR:' *.log

Instead of normal output, prints just the names of input files that contain no matches. For instance, the example prints all the logfiles that contain no reports of errors. This is an efficient use of grep because it stops searching each file once it finds any match, instead of continuing to search the entire file for multiple matches.

-m NUM, --max-count=NUM grep -m 10 'ERROR:' *.log

This option tells grep to stop reading a file after NUM lines are matched (in this example, only 10 lines that contain “ERROR:”). This is useful for reading large files where repetition is likely, such as logfiles. If you simply want to see whether strings are present without flooding the ter- minal, use this option. This helps to distinguish between pervasive and intermittent errors, as in the example here.

-o, --only-matching grep -o pattern filename

Prints only the text that matches, instead of the whole line of input. This is particularly useful when implementing grep to examine a disk partition or a binary file for the presence of multiple patterns. This would output the pat- tern that was matched without the content that would cause problems for the terminal.

-q, --quiet, --silent grep -q pattern filename

Suppresses output. The command still conveys useful in- formation because the grep command’s exit status (0 for success if a match is found, 1 for no match found, 2 if the program cannot run because of an error) can be checked. The option is used in scripts to determine the presence of a pattern in a file without displaying unnecessary output.

-s, --no-messages grep -s pattern filename

Silently discards any error messages resulting from non- existent files or permission errors. This is helpful for scripts that search an entire filesystem without root per- missions, and thus will likely encounter permissions er- rors that may be undesirable. On the other side, it also will suppress useful diagnostic information, which could mean that problems may not be discovered.

Output Line Prefix Control

-b, --byte-offset grep -b pattern filename Displays the byte offset of each matching text instead of the line number. The first byte in the file is byte 0, and invisible line-terminating characters (the newline in Unix) are counted. Because entire lines are printed by default, the number displayed is the byte offset of the start of the line. This is particularly useful for binary file analysis, constructing (or reverse-engineering) patches, or other tasks where line numbers are meaningless.

grep -b -o pattern filename

A -o option prints the offset along with the matched pat- tern itself and not the whole matched line containing the pattern. This causes grep to print the byte offset of the start of the matched string instead of the matched line.

-H, --with-filename grep -H pattern filename

Includes the name of the file before each line printed, and is the default when more than one file is input to the search. This is useful when searching only one file and you want the filename to be contained in the output. Note that this uses the relative (not absolute) paths and filenames.

-h, --no-filename grep -h pattern *

The opposite of -H. When more than one file is involved, it suppresses printing the filename before each output. It is the default when only one file or standard input is in- volved. This is useful for suppressing filenames when searching entire directories.

--label=LABEL gzip -cd file.gz | grep --label=LABEL pattern

When the input is taken from standard input (for instance, when the output of another file is redirected into grep), the --label option will prefix the line with LABEL. In this example, the gzip command displays the contents of the uncompressed file inside file.gz and then passes that to grep.

-n, --line-number grep -n pattern filename

Includes the line number of each line displayed, where the first line of the file is 1. This can be useful in code debug- ging, allowing you to go into the file and specify a partic- ular line number to start editing.

-T, --initial-tab grep -T pattern filename

Inserts a tab before each matching line, putting the tab between the information generated by grep and the match- ing lines. This option is useful for clarifying the layout. For instance, it can separate line numbers, byte offsets, labels, etc., from the matching text.

-u, --unix-byte-offsets grep -u -b pattern filename

This option only works under the MS-DOS and Microsoft Windows platforms and needs to be invoked with -b. This option will compute the byte-offset as if it were running under a Unix system and strip out carriage return characters.

-Z, --null grep -Z pattern filename

Prints an ASCII NUL (a zero byte) after each filename. This is useful when processing filenames that may contain special characters (such as carriage returns).

Context Line Control

-A NUM, --after-context=NUM grep -A 3 Copyright filename

Offers a context for matching lines by printing the NUM lines that follow each match. A group separator (--) is placed between each set of matches. In this case, it will print the next three lines after the matching line. This is useful when searching through source code, for instance. The example here will print three lines after any line that contains “Copyright”, which is typically at the top of source code files.

-B NUM, --before-context=NUM grep -B 3 Copyright filename

Same concept as the -A NUM option, except that it prints the lines before the match instead of after it. In this case, it will print the three lines before the matching line. This is useful when searching through source code, for in- stance. The example here will print three lines before any line that contains “Copyright”, which is typically at the top of source code files.

-C NUM, -NUM, --context=NUM grep -C 3 Copyright filename

The -C NUM option operates as if the user entered both the -A NUM and -B NUM options. It will display NUM lines before and after the match. A group separator (--) is placed be- tween each set of matches. In this case, three lines above and below the matching line will be printed. Again, this is useful when searching through source code, for instance. The example here will print three lines before and after any line that contains “Copyright”, which is typically at the top of source code files.

File and Directory Selection

-a, --text grep -a pattern filename

Equivalent to the --binary-files=text option, allowing a binary file to be processed as if it were a text file.

--binary-files=TYPE grep --binary-files=TYPE pattern filename

TYPE can be either binary, without-match, or text. When grep first examines a file, it determines whether the file is a “binary” file (a file primarily composed of non-human- readable text) and changes its output accordingly. By default, a match in a binary file causes grep to display sim- ply the message “Binary file somefile.bin matches.” The default behavior can also be specified with the --binary-files=binary option.

When TYPE is without-match, grep does not search the bi- nary file and proceeds as if it had no matches (equivalent to the -l option). When TYPE is text, the binary file is pro- cessed like text (equivalent to the -a option). When TYPE is without-match, grep will simply skip those files and not search through them. Sometimes --binary-files=text outputs binary garbage and the terminal may interpret some of that garbage as commands, which in turn can render the terminal unreadable until reset. To recover from this, use the commands tput init and tput reset.

-D ACTION, --devices=ACTION grep -D read 123-45-6789 /dev/hda1

If the input file is a special file, such as a FIFO or a socket, this flag tells grep how to proceed. By default, grep will process these files as if they were normal files on a system. If ACTION is set to skip, grep will silently ignore them. The example will search an entire disk partition for the fake Social Security number shown. When ACTION is set to read, grep will read through the device as if it were a normal file.

-d ACTION, --directories=ACTION grep -d ACTION pattern path

This flag tells grep how to process directories submitted as input files. When ACTION is read, this reads the directory as if it were a file. recurse searches the files within that directory (same as the -R option), and skip skips the di- rectory without searching it.

--exclude=GLOB grep --exclude=PATTERN path

Refines the list of input files by telling grep to ignore files whose names match the specified pattern. PATTERN can be an entire filename or can contain the typical “file- globbing” wildcards the shell uses when matching files (*, ? and []). For instance, --exclude=*.exe will skip all files ending in .exe.

--exclude-from=FILE grep --exclude-from=FILE path

Similar to the --exclude option, except that it takes a list of patterns from a specified filename, which lists each pat- tern on a separate line. grep will ignore all files that match any lines in the list of patterns given.

--exclude-dir=DIR grep --exclude-dir=DIR pattern path

Any directories in the path matching the pattern DIR will be excluded from recursive searches. In this case, the ac- tual directory name (relative name or absolute path name) has to be included to be ignored. This option also must be used with the -r option or the -d recurse option in order to be relevant.

-l grep -l pattern filename

Same as the --binary-files=without-match option. When grep finds a binary file, it will assume there is no match in the file.

--include=GLOB grep --include=*.log pattern filename

Limits searches to input files whose names match the given pattern (in this case, files ending in .log). This option is particularly useful when searching directories using the -R option. Files not matching the given pattern will be ig- nored. An entire filename can be specified, or can contain the typical “file-globbing” wildcards the shell uses when matching files (*, ? and []).

-R, -r, --recursive grep -R pattern path

grep -r pattern path Searches all files underneath each directory submitted as

an input file to grep.

Other Options

--line-buffered grep --line-buffered pattern filename

Uses line buffering for the output. Line buffering output usually leads to a decrease in performance. The default behavior of grep is to use unbuffered output. This is gen- erally a matter of preference.

--mmap

grep --mmap pattern filename

Uses the mmap() function instead of the read() function to process data. This can lead to a performance improvement but may cause errors if there is an I/O problem or the file shrinks while being searched.

-U, --binary grep -U pattern filename

An MS-DOS/Windows-specific option that causes grep to treat all files as binary. Normally, grep would strip out carriage returns before doing pattern matching; this op- tion overrides that behavior. This does, however, require you to be more thoughtful when writing patterns. For in- stance, if content in a file contains the pattern but has a newline character in the middle, a search for that pattern will not find the content.

-V, --version Simply outputs the version information about grep and then exits.

-z, --null-data grep -z pattern

Input lines are treated as though each one ends with a zero byte, or the ASCII NUL character, instead of a newline. Similar to the -Z or --null options, except this option works with input, not output.